(P49) FIBONACCI SEQUENCE AND THE GOLDEN RATIO

In the Fibonacci sequence, each number in the sequence is the sum of the two preceding numbers and continues infinitely. 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144… Fibonacci numbers are considered to be the numbering system of nature, a way of measuring Divinity. As the sequence progresses, this ratio gets closer and closer to a famous irrational number called the „golden ratio”: 1.6180339887, named as such by the Greek mathematician Martin Ohm (1792-1872) in 1835.

This ratio has been frequently observed in dimensional proportions in numerous fields – in architecture, at the Pyramids of Giza and the Parthenon, in the constructions of Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe, in the works of artists Da Vinci, Albrecht Dürer, Juan Gris, Mondrian, and Dalí, in rhythmic durations and height ratios in the works of composers Bèla Bartók, Debussy, Stravinsky, Manzoni, Beethoven.

The same principles apply in rock music. The song „Firth of Fifth” by Deep Purple contains solos that follow the golden ratio, and the song „Lateralus” by Tool has a structure based on the Fibonacci sequence.

In jazz, John Coltrane, Steve Coleman, Mystic Brew, or Ronnie Foster in classic soul-jazz from the 70s, composed pieces with asymmetric structures, in the manner of Fibonacci: „a short chord followed by a long chord, three beats plus five beats, totaling eight beats. It’s a standard four-four time with an additional characteristic – if you step to the rhythm, you hear a chord when you take the first step, then another chord when your knee is lifted between the second and third step.” (Strength in numbers: How Fibonacci taught us how to swing – Vijay Iyer)

Because Western cultures do not really study rhythm in depth, there is no nomenclature for looking at and analyzing rhythms. The only language people have is the language of music notation, which is very limited, and it’s just how things look on „paper”. […] That’s not good. Because rhythm is movement, and it needs to be studied as movement, not as notation. – Steve Coleman

(P50) COLTRANE, EINSTEIN AND THE MISTICISM

Physicist and saxophonist Stephon Alexander has argued in his numerous public lectures and in his book The Jazz of Physics that Coltrane’s music is governed by „the same geometric principle that motivated Einstein’s quantum theory,” while John Coltrane’s friend and mentor, Yusef Lateef, sees in his music a „spiritual journey” that „embraced the concerns of a rich tradition of self-physiological music.”

Coltrane was indeed very passionate about Einstein’s discoveries and enjoyed talking about it frequently. Musician David Amram remembers that the genius behind „Giant Steps” told him that he was „trying to do something similar in music.” However, the great musician spoke too little publicly about the intense theoretical work behind his most famous compositions, probably because he wanted them to speak for themselves. He preferred to express himself philosophically and mystically, relying equally on his fascination with science and various spiritual traditions. Clarinetist Arun Ghosh, for example, saw in Coltrane’s „mathematical principles” a „musical system that connects with Divinity.”

In 1967, John Coltrane entrusted saxophonist Yusef Lateef with a strange diagram that contains the easily recognizable circle of words but illustrates a much more sophisticated scheme than the basic theory of the major scale in music. From this, as pianist Matt Ratcliffe noted, Giant Steps, as well as the Star of David or the Seal of Solomon, can be derived, a very powerful symbolism, especially for ancient knowledge and the Afrocentric direction and ultimately the cosmic consciousness that Coltrane would pursue with the piece A Love Supreme.

In a detailed exploration of the mathematics in Coltrane’s music, saxophonist Roel Hollander argues that examining Coltrane’s drawn circle shows us a „stellar tetrahedron,” „also known as the ‘Merkaba,’ which means ‘light-body-spirit'” and represents „the most intimate law of the physical world.” We find, therefore, an architecture with a great mystical charge in the Coltrane Circle – a „vehicle of divine light supposed to be used by the elevated masters to connect with and reach those who are in tune with higher realms, the spirit/body surrounded by counter-rotating fields of light (wheels within wheels).”

One positive thought produces millions of positive vibrations. – John Coltrane

(P53) ANTHONY BRAXTON AND THE ARCHITECTURE OF MUSIC

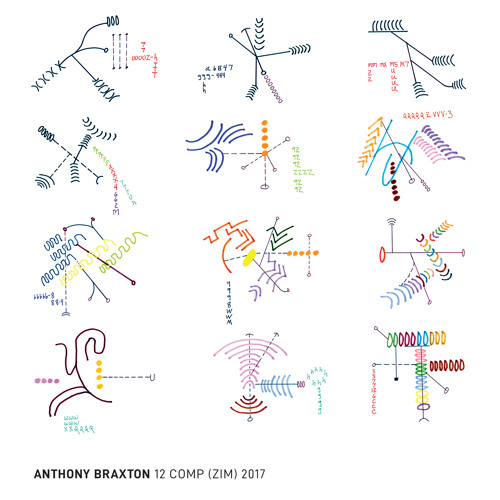

Anthony Braxton is considered a radical instinctual composer who, throughout his career, has positioned himself in creative conflict with old musical protocols. In 1985, Braxton declared that he „sees” each composition „as if it were a three-dimensional painting,” a perception called chromesthesia, which means that he literally „sees” associated sounds, „hearing” shapes and colors. Moreover, in his youth, he used to draw the solos of his favorite saxophonists.

Anthony Braxton is considered a radical instinctual composer who, throughout his career, has positioned himself in creative conflict with old musical protocols. In 1985, Braxton declared that he „sees” each composition „as if it were a three-dimensional painting,” a perception called chromesthesia, which means that he literally „sees” associated sounds, „hearing” shapes and colors. Moreover, in his youth, he used to draw the solos of his favorite saxophonists.

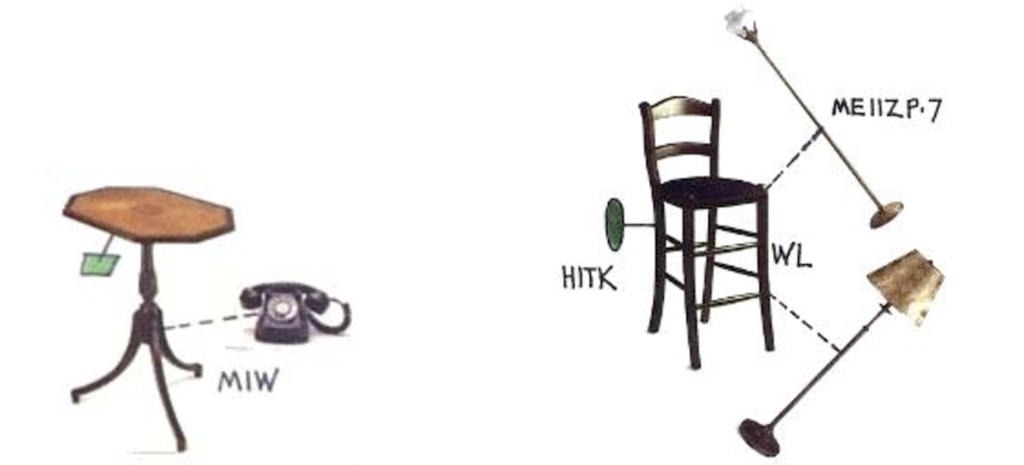

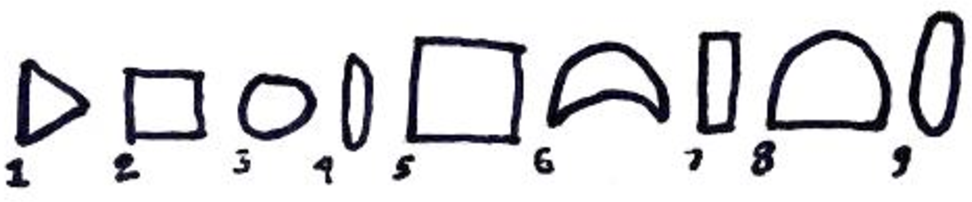

Each of the five volumes of his composition notes begins with a list of „sound classifications,” which he compiled into a basic musical vocabulary. There are almost 100 classifications, from „curved sounds” to „gurgling sounds” and „petal sounds,” each with its own visual name. Braxton attributes a visual title to each work: a diagram consisting of a mixture of lines, shapes, colors, figures, numbers, and letters that encode both the structural elements and what he calls the „vibrational” elements of music.

He maintains that, in most cases, fusion involves „a visual sensation caused by auditory stimulation.” „I don’t just hear sounds, but spectra… I perceive sound in three dimensions. I didn’t even realize this until I took listening courses in college and realized that I wasn’t hearing what everyone else was hearing,” said Anthony Braxton.

Another concern of Braxton’s is for „ancient” cultures, explaining that this interest is related to the fact that numerous ancient cultures, from ancient Egypt and China to European Renaissance hermetism, considered music part of a network of mystical correspondences that includes not only colors and shapes but also astrological signs, numbers, hours, body parts, elements, seasons, and planets.

Braxton explained how these correspondences work in Composition #76: according to astrology, each sign is associated with both a color and a set of emotional characteristics – for example, Taurus is associated with green and feelings of calm and restraint, while Aries is associated with red and intense and explosive emotions. Therefore, in the score of #76, colors signal those corresponding emotions: green indicates calm musical interpretation, red indicates intense interpretation, etc. Various shades of color mark factors such as dynamics and tempo: the darker the shade, the faster and/or louder it is interpreted.

Composition #76, written in 1977, announced a new phase in Braxton’s music, which placed even greater emphasis on the use of „visual” notations. Compositions #78 and #84, for example, are almost entirely graphic scores: #78 is a „workshop” whose main purpose is to encourage performers to become familiar with the use of shapes and colors as guides for improvisation, while #84, dedicated to Picasso, includes nine given forms arranged in various configurations.

Synesthesia = Association between sensations of different nature that give the impression that they are symbolically related to each other.

Chromesthesia = Processing sounds like colors.

Hear with your eyes. See with your ears. – Charlie Parker

Images source: semanticscholar.org